When Philip II became king of Macedonia in 359 BCE, he inherited an army that was relatively ineffective. He immediately initiated a series of military reforms.

Together, Alexander and his father would create an army unlike anything the ancient world had even seen. Previous wars such as the Persian and Peloponnesian War had demonstrated that the old ways were no longer dependable. Philip took a poorly disciplined group of men and turned them into a formidable army

. Most historians believed Philip developed his ideas while a hostage in Thebes, observing their notorious Sacred Band. To begin with, he increased the size of the army from 10,000 to 24,000, and enlarged the cavalry from 600 to 3,500; this was no longer an army of citizen-warriors. In addition, he created a corp of engineers to develop siege weaponry such as towers and catapults.

Later, Alexander would use these siege towers with devastating effect at Tyre (6,000 would be killed and 30,000 enslaved).

Siege of Tyre

The victory at Issus against the Persians opened the road for Syria and Phoenicia for Alexander the Great’s Army. In early 332, Alexander sent general Parmenio to occupy the Syrian cities and himself marched down the Phoenician coast where he received the surrender of all major cities except the island city of Tyre which refused to grant him access to sacrifice at the temple of the native Phoenician god Melcart. A very difficult seven-month siege of the city followed.

Acropolis Museum, Athens.

![Siege of tyre]](https://www.hellenic-art.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/7ae2d3c199a4c742282fc638b4b2e6f9.jpg)

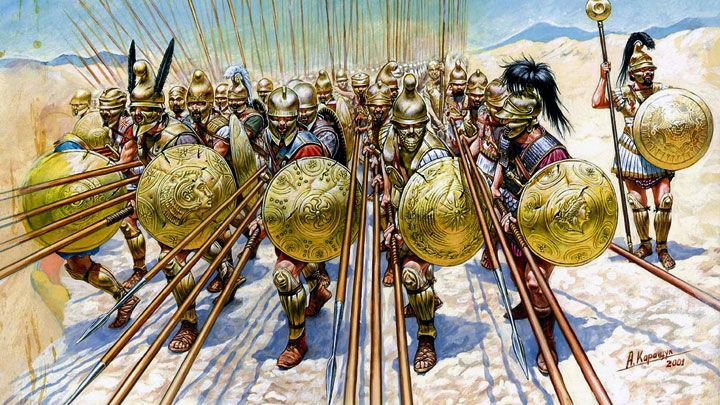

Macedonian Phalanx wielding the sarissa

Macedonian Phalanx

The very nature of the phalanx required constant drilling, and both men demanded strict obedience; punishments would be meted out for those who disobeyed.

Like Alexander after him, Philip required an oath of swearing allegiance to the king. They provided uniforms (Greek armour) – a simple idea that gave each man a sense of unity and solidarity.

Besides the obvious, there was logic behind what they did; each soldier would no longer be loyal to a particular province or town as now he would be loyal only to the king. The battle-hardened men who fought for Philip and Alexander had to remain dedicated to his king and the glory of Macedonia.

This loyalty and restructuring became evident at Philip’s victory over Athens and Thebes (with the help of an eighteen year old Alexander) at the Battle of Chaeronea; a battle that demonstrated the power and authority of Macedonia.

Philip completely restructured the army. The first order of business was the reorganization of the phalanx, providing each individual unit with its own commander – thereby allowing for better communication.

The fundamental fighting unit became the taxes which usually comprised 1,540 men and commanded by a taxiarch.

Every taxis was broken into distinct subdivisions. A taxis was composed of three lochoi (each commanded by a lochagos)o r 512 men apiece. 32 dekas (a line of ten men – later sixteen) made up each lochoi.

Each man occupied only two cubits of space until actual battle, when he used only one cubit.

Weapons & Tactics

Next, Philip changed the principal weaponry from the hoplite spear to the sarissa – an 18-20 feet pike; it had the advantage of reaching over the much shorter spears of the opposition. Obviously, the length of the sarissa made it difficult to handle, demanding both strength and dexterity.

The hoplite now became a pezhetairoi or foot companion. Like his predecessor, he, too, carried a shield or aspis – similar to the hoplon, but due to the size of the sarissa (one had to use both hands); it was carried by a sling over the shoulder. Besides the sarissa, each man possessed a smaller double-edge sword or xiphos for close-in-hand fighting.

There was only one drawback to the phalanx – it worked best on flat, unbroken country; however, despite this disadvantage, Alexander used it with amazing success. In almost every campaign the formation of Alexander’s army remained the same; however, due to the nature of the field of battle, some changes were made at Hydaspes where archers led the field against Porus’ elephants.

The pezhetairoi were in the center; the hypaspists were to their right with the cavalry on either flank. Archers and additional lighter infantry served on outer flanks and in the rear.

The pezhetairoi were indoctrinated to maintain ranks in all circumstances, although they were able to break smoothly when necessary; this was evident at Gaugamela against Darius’ scythed chariots. In battle, the five front ranks lowered their sarissa parallel to the ground while the rear ranks (usually wearing broad-brimmed a straw hat or kausia instead of helmets) carried theirs upright.

To the right of these pezhetairoi were the far more mobile hypaspists also called shield-bearers. Although not as heavily armed – carrying only a shorter spear or javelin – they served a special role in both Philip and Alexander’s army.

They were recruited for their skill and physique, requiring a special level of training. They were mostly from the peasantry of Macedon and, thereby, had no tribal or regional affiliation meaning they loyal only to the king himself.

There were three distinct classes of hypaspists – the “royal” who served as the bodyguards of the king as well as guards at banquets and official events, an elite force known as the argyraspids, and finally the actual hypaspists corp.

A special band of veterans within the hypaspists would become known as the Silver Shields.

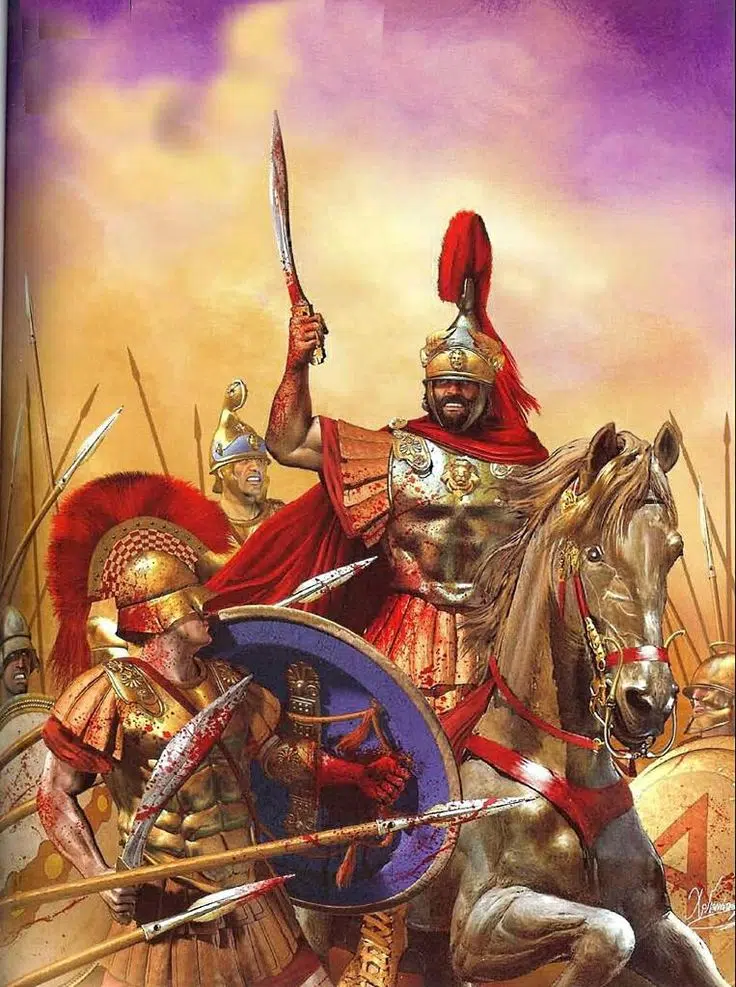

Cavalry

On both the right and left flanks were the cavalry. The cavalry was the army’s main strike force and would make the decisive breakthrough of the enemy lines – this was evident at the battles of Granicus, Issus and Gaugamela.

There were two divisions of the cavalry – the Companion and the prodromoi – the latter was the more flexible and versatile Balkan cavalry which was used primarily as scouts.

The Companion Cavalry was the more important division and was commanded at first by Philotas and later by Cleitus and Hephaestion. They were divided into eight squadrons of 200 men each and each man carried a nine-foot lance but wore little armor.

Due to the extreme value of the cavalry – 1,000 horses would die at Gaugamela – a steady supply of extra horses was kept at all times. Of course, the most important of these squadrons was that of Alexander. Alexander and his Royal Companions always fought on the right while Parmenio commanded the Thessalian Cavalry on the left flank.

Tactics remained simple – the pezhetairoi would hit the center of the opposing army in an oblique angle while the cavalry would attack and punch holes on the flanks.

As with the previously abandoned hoplite phalanx, the new army was designed to attack and remained a purely offensive weapon. While well-trained soldiers are always essential for success, an army needs capable leadership, and besides Alexander, the force that crossed the Hellespont had several capable officers, namely Parmenio, Perdiccos, Coenus, Cleitus, Ptolemy, and Hephaestion.

Before Philip and Alexander, the Persians under Darius I and Xerxes had been repelled by a smaller force – these men of Greece fought unlike anyone and anything the Persians had ever experienced.

By the time of Alexander, the fighting force that took him across both Greece and Persia had been perfected. He crossed Asia into India, often fighting a force that outnumbered him. His use of the phalanx and cavalry, combined with an innate sense of command, put his enemy on the defensive, enabling him to never lose a battle.

His memory would live on and his determination brought the Hellenic culture to Asia. He built great cities and changed forever the customs of a people

Find out more about the Greek Culture and history on the website of the greek art shop Hellenic Art!

Source: Donald L. Wasson, Ancient History Encyclopedia.